Table of Contents

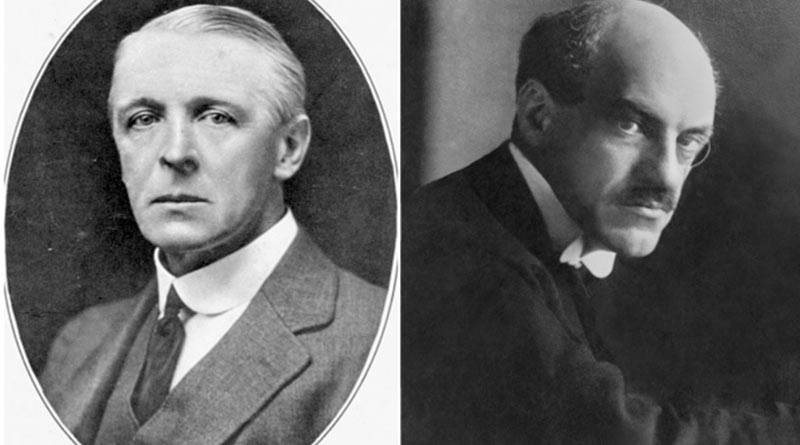

Government of India act, 1919 (Montague-Chelmsford Reforms)

Introduction:

The Government of India Act 1919 was an Act passed to expand the participation of the Indian people in the government. The Act has the recommendations of The Secretary of State for India- Edwin Montagu and the Viceroy-Lord Chelmsford widely known as The Montague-Chelmsford Reforms. The Act was for ten years (1919 -1929). This Act was already set to be reviewed by The Simon Commission after Ten Years. The Act provided for a Dual System of Government wherein all the government-controlled activities were divided into two lists: The Transferred List and The Reserved List. The Transferred List contained minor activities such as health, and education etc under the control of Indian’s while The Reserved List contained all major government activities such as finance, military, communication etc.

Background:

Edwin Montagu had become The Secretary of State for India in June 1917. Edwin Montagu, The Secretary of the State put before the Cabinet a proposal regarding his intention to work towards the gradual development of free institutions in India to ultimate self-government. Lord Curzon suggested that instead of development of free institutions Edwin Montagu should try to work towards increasing association of Indians in every branch of the administration and the gradual development of self-governing institutions. The Cabinet was satisfied with Lord Curzon’s views and approved The Secretary of State for India Edwin Montagu’s plans with Lord Curzon’s views.

Features of Government of India Act 1919

- This Act introduced a separate declaration that the objective of the British Government was the gradual introduction of responsible government in India.

- Diarchy was introduced at the Provincial Level. Diarchy means a dual set of governments where one set of government was accountable while the other was not.

- Subjects of the provincial government were also divided into two groups. The reserved subjects were controlled by the British Governor of the province while the transferred subjects were given to the Indian ministers of the province.

- The act made a provision for differentiation of the central and provincial subjects.

- The Act specified Income Tax as a source of revenue for the Central Government.

- No bill of the legislature could be passed without the assent of The Viceroy. However, The Viceroy could enact a bill without the legislature assent

- This Act made the central legislature bicameral. The lower house was the Legislative Assembly, with 145 members serving three-year terms and the upper house was the Council of States with 60 members serving five-year terms.

- The Act provided for the establishment of a Public Service Commission in India.

- The communal representation was extended to include Sikhs, Europeans and Anglo-Indians. The Franchise (Right of voting) was also granted but only to a limited number of people.

- The seats were distributed among the provinces not upon the basis of the population but on the governmental importance.

- The number of Indians in The Executive Council was three out of eight.

- It established an office of the High Commissioner for India in London.

- The Secretary of State and the Governor-General could interfere in matters under the reserved list, but could only do so up to a limited extent in the transferred list.

- The Transferred List contained Local Self Government, Public Works, Sanitization, Industrial Research and setting up of new factories.

- The Reserved List contained Justice Administration, Press, Revenue, Forests, Labour Dispute Settlements, Water, Agricultural Loans, Police, Prisons etc.

Voting Power:

The following conditions were present in the act before anyone could vote

- The Voters should have paid land revenue of Rupees Three Thousand /More, have a rental value property/have taxable income.

- They should have Legislative Council Members.

- They should be University Senate Members.

- They should be elected to local bodies and have an office.

- Some specific titles should be held by them like Raja, Prince, Chief, Collector etc.

Merits of The Government of India Act 1919 :

The following were the merits of The Government of India Act 1919

- Dyarchy introduced the concept of responsible government.

- The Concept of the federal structure was introduced.

- In the administration, Indian participation increased.

- Elections were held for the first time which created Indian political consciousness. Some women got the right to vote, for the first time.

Limitations of the Government of India Act 1919 :

The following were the limits of The Government of India Act 1919

- This act increased integration and representation of specific caste and religion.

- The base of the voting franchise was very small. It did not extend to the common man.

- The governor-general and the governors had a lot of power to suppress the legislatures and the provinces.

- Allocation of the seats for the central legislature was not based on population but on religion and importance.

- The divisions of departments were not properly distributed.

- No real power was given to the elected Indian Ministers.

- The Rowlatt Act(curtailing of powers of press and media along with imprisonment of someone for as long as they wished, no seeing of lawyers and no appeals to the government popularly known as na appeal.na dalil,na Vakil translated as No Appeal, No Judge and No lawyer in India) .The Rowlatt Act was passed by The Defence of India Act 1915 to curtail the nationalist and revolutionary activities which happened during and the aftermath of the First World War. The Rowlatt Act was passed in 1919 even though there were protests and resignation in the legislative Council.

Conclusion:

Thus, we can conclude by saying the Government of India Act 1919 provided a very limited transfer of power through dual system governance. It also developed the flooring for Indian federalism, as it identified the provinces as units of general administration. The changes at the provincial level were of importance, as the legislative councils had a majority of elected Indian members. In the pursuit of maintaining a dual governance system, the nation-building departments of government were placed under Indian ministers who were individually responsible to the legislature. The departments that made up the main structure of British rule were retained by executive councillors who were nominated by the Governor. They were often British and were responsible to the governor.

Author: Samar Jain,

SYMBIOSIS LAW SCHOOL 1ST YEAR